BEYOND THE BASSLINE: 500 YEARS OF BLACK BRITISH MUSIC

THE BRITISH LIBRARY

26 APRIL 2024 - 26 AUGGUST 2024

Showcasing 500 years of Black British music, Beyond The Bassline at the British Library brought together a multitude of artefacts, artworks, and music in an exhibition based on its counterpart publication of the same name. The exhibition aimed to tell the story of Black music in Britain and the legacy of this history from Tudor England to modern Grime and was the culmination of a huge research piece by Dr Aleema Gray and Dr Mykaell Riley, drawing mostly from the collection of the library. While the exhibition was highly informative, visually and aurally stimulating, and created nostalgia for many exhibitiongoers, the show felt rushed, missed out large portions of the history of Black music in Britain and lacked real nuance in how it portrayed Black culture by homogenising Blackness, seemingly to make it more palatable to their largely white members. These curatorial failures ultimately undermine the exhibition’s primary goal in educating about Black history to create racial equity and therefore show unethical curatorial methods and delivery.

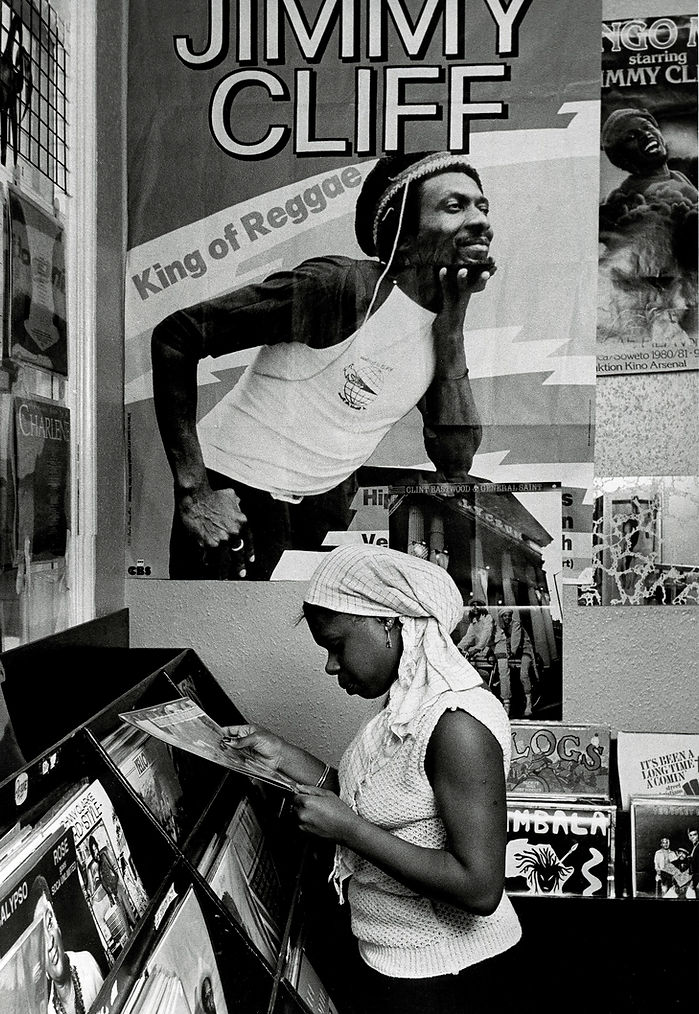

Beyond The Bassline offers an overview of the history of Black British music, formatted as a chronological retrospective. The show begins with discussion of Black people in England in the 16th century, briefly showing the history of the Black influence in Henry VIII’s court, moving on to the changing attitudes towards Blackness as racism developed alongside the slave trade, as shown in the section entitled The Ocean (1500s-1870s). This quickly moves on to telling the story of more recent music, with “On Stage (1880s-1960s), The Frontlines (1950s-1980s), In the Record Shop (1960s-1980s) and Cyberspace (1990s-2020s). Each section is ‘interrupted’ by new soundscapes, artworks and films created by artists and community collectives from around the UK” (Artplugged, 2024). Being based on the history of music, the show featured extensive opportunities to listen to songs with a particularly notable history, such as 1940s Black wartime Jazz, 1980s Notting Hill Carnival music, and 2000s early Grime. It also showed music-related artefacts including clothing and outfits, protest materials and album art and included original commissioned pieces of poetry and film to supplement the historical narrative, specifically a “film piece by Roundhouse Young Filmmakers encased in a bespoke soundsystem built by Friendly Pressure; a series of mosaics channelling Rastafari culture; a textile work showcasing the spirit of resistance in Leeds; and a piece by Jukebox Collective that blends moving image and dance along the south Wales coast” (Williams, 2024).

The aim of the exhibition was to “expand what perceptions of Black British music is [by] looking at music as a conversation… as a vehicle for community” (Gray by Muk, 2024). Curated by Gray and Riley, the exhibition exemplifies an exclusive practice, at it utilises curatorial authority delivered by a distinct expert or group of experts who gatekeep the topic by delivering only their interpretation of the works and information. the curators had the intention of delivering a holistic overview of 500 years of Black British music as presented in the accompanying book written by Paul Bradshaw. It is relevant to note that Bradshaw, a music journalist and writer, is a white man – this is questionable as to write a book about Black British music seems to necessitate an implicit understanding of Blackness and Black culture, as established as a part of ethical curation or research previously in this essay. This undermines the exhibition directives and exclusive practice undertaken by Gray and Riley, as they are gatekeeping Black history that has been written from a white perspective which “lends itself to the fact that white people are still very much in charge of these curations” (Hanson-Ellesse, 2024).

The curatorial design of the exhibition failed to provide the full picture of Black British music for several reasons. The exhibition was too small and felt rushed when moving around it. The section named The Ocean (1500-1870) was notably small in comparison to the other sections of the show, especially considering it spanned the greatest time. of course, there will be limited information from this period and less physical artefacts in the British Library’s collection, and in general. However, there was room for more explanation and contemporary interpretation of this era of history’s relationship with Blackness in music. This lack of information and suddenly being thrust into the late 19th century left the exhibition feeling hurried form the very start. This hurriedness left one wondering if they had only included this section so they could label the exhibition as 500 years of Black British music for marketing and ticketing purposes so as to attract a broader audience and make the exhibition sound fuller and vaster than it was – in actuality, it focused on Black British Music from the eve from the 20th century until contemporary times, mainly focusing on the 20th century. This is exploitative of Black British history as it is being used for financial gain, thus suggesting unethical curatorial practices. It may be the case that this is not a decision made by the curators themselves but by the governing bodies and funders of the British Library who are largely White, as funders require certain metrics (such as numbers of tickets sold, key point indicators showing the reach of exhibition marketing, net profits, etc.) that make them inflexible in their approach to exhibition delivery (Hanson-Ellesse, 2024). This thus causes the “[alienation of] black people through the way that they try and advertise to their [white] patrons” (Hanson-Ellesse, 2024). Despite funders being financially necessary for most PWCI and their endeavours, “we have to avoid brand partnerships, we have to avoid patrons, we have to avoid sponsorship, we have to avoid embassies we have to… avoid all kinds of funders unless they are an arts organization who can stand with imputed communities and back [a community-centred] approach” (Carroll, 2024). While this is a limiting and polarised standpoint, it is important to note that funders and those in directorial positions at PWCI can hinder ethical curatorial practice by prioritising financial outcomes.

The small size of the exhibition also meant that there was a lack of inclusion of aspects of Black British music history, as well as missing key aspects of current Black British music. One must note that “Surveying 500 years-worth of any sort of music is no easy feat. But tackling the history of Black British music is near impossible – not least because of its legacy permeating nearly every instance of contemporary pop and underground culture” (Wilkinson, 2024). Despite this, there was a distinct lack of mention of the modern influence of African American and Caribbean music on the current Black British scene. It could be assumed that the exhibition was discussing the historical influence of other Black diasporic cultures on British music up to the contemporary era, however given the commentary on the influence of the Caribbean on British carnivals, and the importance of African American Jazz regarding all British Jazz, it seems remiss to ignore the American and Caribbean influence on Grime, Drill, UK Garage and more. This lack of inclusion implied that there is no modern cross-cultural influence which does a disservice to the rich musical exchange that takes place between Black diasporic communities. Gray on this topic mentioned that

“we tend to look towards America when thinking about popular Black music, because it has dominated pop music and a lot of our ideas around Black culture. It was interesting to see a map of our own story emerge through this journey – lovers’ rock, jungle, garage, grime – Black British music genres that were fostered and created in Britain.” (Gray to McKay, 2024)

Here Gray acknowledges the effects of American music on Black British music and alludes to the decision to not include some of the American influence on it as intentional to shed light on how Black British music is from within Britain. I believe that the lack of inclusion of this topic fails to show the importance of contemporary cultural exchange and waters down the story of Black British music. One can understand that a line has to be drawn, not everything can be included, however it seems that the line of inclusion for this exhibition is arbitrary at best, and intentionally diminishing the Black experience of cross-cultural exchange at worst.

This lack of inclusion of information, likely due to the limited size of the exhibition and its vast scope, is evidenced through the omission of modern Black British music other than Rap, Hiphop or UKG and UK Funky. There is a sprawling scene for Black Jazz, classical, experimental, soul, punk, amongst many other genres that were not mentioned in this show that aimed to discuss Black British music holistically. This failure to include genres that are not perceived as inherently Black is reductive as it plays to stereotypes that Black music is rap. This stereotype follows to racial typecasting of the idea that Black music is ‘aggressive’ music, such as genres like Grime and Drill which infer that Blackness is related to aggression, largely due to the content of the lyrics and the genres’ relations to gang crime. This is a harmful racist stereotype and fails to portray Black music and thus Blackness as varied, nuanced and cross cultural within the Black community. Again, it is arguable that this approach intentionally homogenises Blackness, making it more palatable and accessible to white audiences who may hold implicit racial biases. While the exhibition intends to portray Black culture and history, PWCI “[don’t] actually understand what a Black community looks or sounds like. Therefore, spatial infrastructure and programmes are often tone-deaf” (Banson, 2024). If there was more consultation with the wider Black community, and if the exhibition had not been based on a book that came from a white perspective, perhaps it would have felt more well-rounded and accessible to Black people, as well as provided with more knowledge than what is mostly common knowledge for Black British people with an interest in music.

These curatorial decisions suggest some aspects of unethical curation around race and blackness. By watering down the Black British experience and not including aspects of The Culture, it is possible that this is an intentional curatorial decision possibly to make Blackness more palatable and accessible to white audiences and thus more profitable. This is an historic precedent set by PWCI in their whitewashing of content and history which is the primary issue Entangled Pasts attempted to address and counteract as an antiracist exhibition. Whitewashing and diluting black content for white audiences ultimately fetishes blackness by commodifying it for the purpose of ticket sales, which is exploitative and therefore unethical. Beyond The Bassline also made little mention of the intersectional aspect of race which would have come into play in terms of access to music creation and culture – the show featured the work of many Black women however within the exhibition materials and the descriptions accompanying work there was very little acknowledgement of the power structures that affect certain marginalised people in different ways.